In both papers, new tools introduced in the last 10 years have been integrated Both the American and European expert panels propose a risk-dependent strategy:

• recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone (rhTSH) as an alternative for the withdrawal (WD) of thyroid hormone in order to obtain a high thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH);6 and

In both papers, new tools introduced in the last 10 years have been integrated Both the American and European expert panels propose a risk-dependent strategy:

• recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone (rhTSH) as an alternative for the withdrawal (WD) of thyroid hormone in order to obtain a high thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH);6 and

• neck u/s as a sensible tool for the detection of residual or recurrent locoregional disease.7–9Of course, the value of guidelines in the approach to DTC patients ncreases along with the accumulating data on the outcome of DTC, depending on treatment variables.10,11

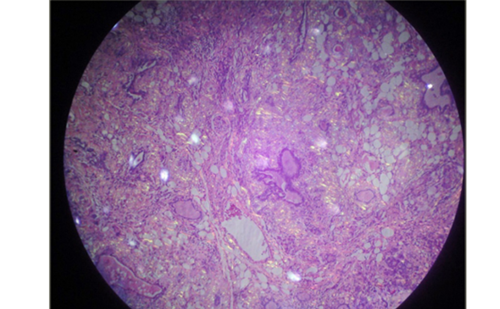

Pre-surgical Diagnostic Approach and Surgical Management -Impact of Fine-needle Aspiration Cytology Findings on the Type and Extent of Surgery‘Follicular Neoplasm’

When FNAC is indeterminate and thus suggests a ‘follicular neoplasm’, surgery is indicated. However, the dilemma of a lobectomy versus a total thyroidectomy has not yet been resolved. Neither the ATA guidelines nor the ETA consensus statement presents a straightforward strategy Nevertheless, both point to similar additional factors that are taken into account in the decision process: clinical risk factors, the presence/absence of contralateral thyroid nodules and patient preferences.4,5 Both the US and European expert panels agree on the indication of a total thyroidectomy in case of clinical suspicion of malignancy (e.g. fixation, hoarseness, etc.) or in the presence of clinical risk factors of malignancy (large tumours >4cm, family history of thyroid cancer, history of radiation exposure). Agreement is also present on the indication of a total thyroidectomy in the presence of bilateral nodular disease and on the mportance of the preoperative u/s characteristics (of the nodule as well as the contralateral lobe and lymph nodes (LNs))Papillary Thyroid Cancer

As expected, in case of FNAC diagnostic for malignancy – PTC – the ATA guidelines and the ETA consensus agree on the indication of a total thyroidectomy as the standard surgical treatment. Controversy persists, however, regarding the matter of microdissection of LNs. According to the ATA guidelines, routine bilateral central (compartment VI) node dissection “should be considered” for patients with PTC and suspected Hürthle cel cancer, since it may improve survival and reduce recurrences. The European consensus states: “compartment-oriented microdissection of lymph nodes should be performed in cases of pre-operative suspected and/or intra-operatively proven lymph node metastases”. Moreover, the result of LN

Adapted With Permission

|

Table 1: Indication, Activity and Method of Radioiodine Ablation According to Risk Stratification |

|||

| European Consensus | ATA Management Guidelines | ||

| Indication | >T1b I Probable → | >T3 or N1 or M1 Define |

Selected stage I Most Stage II All Stage III |

| Activity necessary | 30-100mCi → | >100mCi |

minimal activity 100–200mCi if residual microscopic disease/ more aggressive tumour histology |

| Withdrawal versus rhTSH | rhTSH → | Withdrawal | Withdrawal or rhTSH |

dissection is an important factor in the risk stratification and risk-dependent post-surgical strategy as proposed by the ETA consensus (see below)Post-surgical ManagementThe ‘Old’ Universal Standard

The standard protocol for post-surgical management of DTC, reviewed by Schlumberger et al.1 and used until recently, is schematically represented in Figure 1The first step is radioiodine ablation (large activity, 100mCi I131) of the thyroid remnant in a setting of thyroid hormone (WD), followed by a total body scan (TBS). Radioiodine remnant ablation is proposed in most patients except in unifocal PTC <1cmThe second step consists of the evaluation of cure and the long-term surveillance for disease recurrence. Six to 12 months post-surgery, the patient is again withdrawn from thyroid hormone. Four to five weeks later a blood sample is taken to measure serum thyroglobulin (Tg) and a diagnostic dose of radioiodine is administered to evaluate the residua uptake of radioiodine by TBS. In case of uptake outside the thyroid bed, representing residual disease, further treatment is indicated. Fortunately, in the majority of patients no, or very limited, residual uptake in the thyroid bed is present. In this case, the serum Tg level should be evaluated, serving as a tumour marker. An undetectable level (<1ng/ml)ndicates cure, whereas a Tg (10ng/ml indicates a high risk of residua disease and need for further investigation/treatment. In case of an intermediate value (1-10ng/ml) follow-up is warranted, since one-third of these patients will progress with rising Tg levels if the procedure is repeated after two years. Two-thirds of this patient group do not progress and their Tg level will decline, probably as a late consequence of the initial radioiodine therapy.This scheme can be called the universal standard for post-surgical follow-up, since published outcome data are in agreement with this protocol.2,3 On the other hand, this scheme could be called the hard old standard, ncluding repeated (at least two) episodes of hypothyroidism (being nconvenient for the patient) and lifelong TSH-suppressive therapy (not only being hardly tolerable for several patients, but also increasing the risk of osteoporosis and cardiac arrhythmia)

Refinements and New Tools Introduced in the Last Decade

Two major advances in recent years have enabled clinicians and patients to avoid some inconveniences of the previous management protocol recombinant human TSH (rhTSH) and u/s

ATA Guidelines and ETA Consensus Regarding rhTSH and its Indications

With the development of rhTSH, it is nowadays possible to reach increased TSH levels, with the difference being that TSH is not endogenously produced but exogenously administered, allowing continuation of the thyroid hormone treatment. Two injections of rhTSH (Thyrogen® 0.9mg, Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.) result in TSH levels comparable to the levels obtained after WD. Side effects are minor, and the major side effects of WD – symptomatic hypothyroidism – can be avoided.12According to the universal standard, two episodes of high TSH are needed. In step one – the therapeutic step – high TSH necessarily precedes treatment with a high dose of radioiodine, aiming at maxima radioiodine uptake by the remnant tissue.In step two – the diagnostic step – high TSH is needed for optimal iodine uptake (TBS) or Tg production (serum Tg measurement) by remaining local or distant cancer cells. In both the diagnostic and therapeutic steps, rhTSH had to prove its equivalency to the withdrawal method before its approvalConcerning the diagnostic use of rhTSH, a randomised study showed that rhTSH and WD are equally sensitive and specific for the detection of residual or recurrent DTC. This is the case provided a lower cut-off value for Tg is used after rhTSH compared with the cut-off values used after WD. The inpatient comparison showed that Tg values after WD of 10ng/ml correspond to values between 2 and 5ng/ml after rTSH.13 The diagnostic use of rhTSH has been included in the ATA guidelines and the ETA consensusConcerning the therapeutic use of rhTSH, there is one randomised study limited to low-risk patients. This study shows equal ablation rates in both groups.14 The therapeutic use of rhTSH has been approved by the European Medicines Agency and was introduced in the ETA consensus for low-risk patients. In the flow chart proposed by the ATA, the therapeutic use of rhTSH is proposed as an alternative to WD. The footnotes are more restrictive since the therapeutic use is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and since the majority of the authors retrieved themselves from the discussion because of varying degrees of involvement with the Genzyme Corporation, the manufacturer of rhTSH (Thyrogen®)

The Role of Ultrasound in Post-operative Follow-up

A sensitive method to locate residual or recurrent LN disease is u/s. The reported sensitivity varies between 90 and 96%.8,9 For LN disease, u/s is even more sensitive than diagnostic TBS. The problem with u/s lies in its lack of specificity and the difficulties in discerning metastatic from reactive LNs. In order to obtain proof that the LN demonstrated by u/s is metastatic, FNAC can be performed. However, this technique raises the problem of frequent inadequate samples and therefore should be completed with the collection of the needle-washout for detection of Tg.15,16 Due to its very high sensitivity to detect neck recurrences, u/s has been introduced in post-operative follow-up algorithms. According to the ATA guidelines, u/s is considered the number one examination in the follow-up of the majority of DTC cases, combined with a serum Tg measurement three months after ablation. No explicit description is mentioned where u/s findings alter the management.4 Also, in the algorithm proposed by the ETA, u/s is high in the ranking of examinations and accompanies the rhTSH-stimulated Tg value in the planning of follow-up (see Figure 2). In this consensus report, the authors advise u/s-guided FNAC for suspicious findings >0.5cm and u/s follow-up some months later for suspicious findings <0.5cm.5 However, the procedure of the FNAC samples is not mentioned and the advice of the authors is, probably, a FNAC for conventional cytology supplemented by determination of Tg in the needle-washoutRisk-tailored Strategy – Resulting in a New Standard Protocol

Contrary to the universal standard post-surgical management, which is risk-independent (except for the exclusion of unifocal microPTC), the recent European consensus and ATA guideline standard take into account the very initial staging, determining the indication (and procedure) for ablation of the thyroid remnant

Flow chart for the follow-up after initial treatment (surgery and radioiodine ablation).

*If basal Tg is detectable there is no need for rhTSH simulation and the patient needsimaging and/or therapy.

***In the text a cut-off of 2ng/ml is suggested.Adapted With Permission

| Table 2: Risk Stratification | ||

| European Consensus | ATA Management Guidelines | |

| Very low | T1 <1cm N0 M0 | |

| Low | T1 >1cmT2N0 M0 | No local or distant metastasisAll macroscopic tumour resectedNo aggressive histology/vascular invasion postablation TBS: negative |

| intermediate | Microscopic invasion into Perithyroid tissue Aggressive histology Vascular invasion | |

| High | >T3>N1 or M1 | Macroscopic tumour invasionncomplete tumour resection Distant metastasis Post-ablation TBS showing radioiodine uptake outside thyroid bed |

| Table 3: Indication and Degree of Thyroid-stimulating Hormone-suppressive Therapy According to Risk Stratification | |||

| European Consensus | ATA Management Guidelines | ||

| Initial | Low-risk | <0.1 | 0.1-0.5 |

| High-risk | <0.1 | ||

| Long-term | Low-risk Free of disease | 0.5-1.0 | 0.3-2.0 |

| High-risk Free of disease | <0.1 | 0.1-0.5 | |

| Residual disease | <0.1 | ||

TSH is expressed in mu/l.Step One – Radioiodine Ablation – A Risk-dependent Strategy

The indication and method of ablation as proposed by the ETA consensus and ATA guideline paper respectively is schematically represented in Table 1.Regarding the European consensus, two patient groups have to be discerned: the high-risk and the low-risk patient group. In the high-risk patient group, radioiodine has been proved to reduce the recurrence and mortality risk and in this group the indication for the ‘old’ standard ablation (>100mCi after WD) is definite. In the low-risk group, however, the goal of ablation consists in reduction of the recurrence risk and mprovement of diagnostic accuracy (see Table 2). In this group, the assumption is that preparatory rhTSH and/or a lower radioiodine activity is probably as good as the ‘old’ standard ablation.The ATA guideline indicates radioiodine ablation depending on the Tumor, Node, Metastases/American Joint Committee on Cancer, sixth edition (2002) risk groups and is therefore more restrictive regarding the use of rhTSH (see above).

Step Two – The New Follow-up Schemes

Exemplified by the follow-up scheme of the ETA consensus paper (see Figure 2), rhTSH-stimulated Tg and u/s are central to the follow-up as described above. The rhTSH-stimulated Tg cut-off value indicating a high risk of residual disease and need for immediate imaging and/or treatment is called ‘institutional’. In the text a rhTSH-stimulated Tg value of >2ng/m is proposed.

TSH Substitution-Suppression Therap

Treatment phase and risk group are the determinants for the proposed TSH goal (see Table 3).

Conclusion

The 2006 ATA guidelines and ETA consensus integrate new tools in the management of DTC and provide a risk-tailored strategy. These new management guidelines have several implications for the surgica management and follow-up of DTC patients. The universal standard for the follow-up of DTC patients as published in 19981 is the benchmark, but is modified and refined according to outcome data and new advances: rTSH and u/s.All of these advances aim at a total removal of the tumour at the first surgery, allowing accurate staging that determines the following risk-dependent strategy and follow-up, thereby minimising the risk of recurrence, metastasis or cancer-related death on the one hand, but also minimising unnecessary side effects of treatment on the other hand.